Helen (1886-1982)

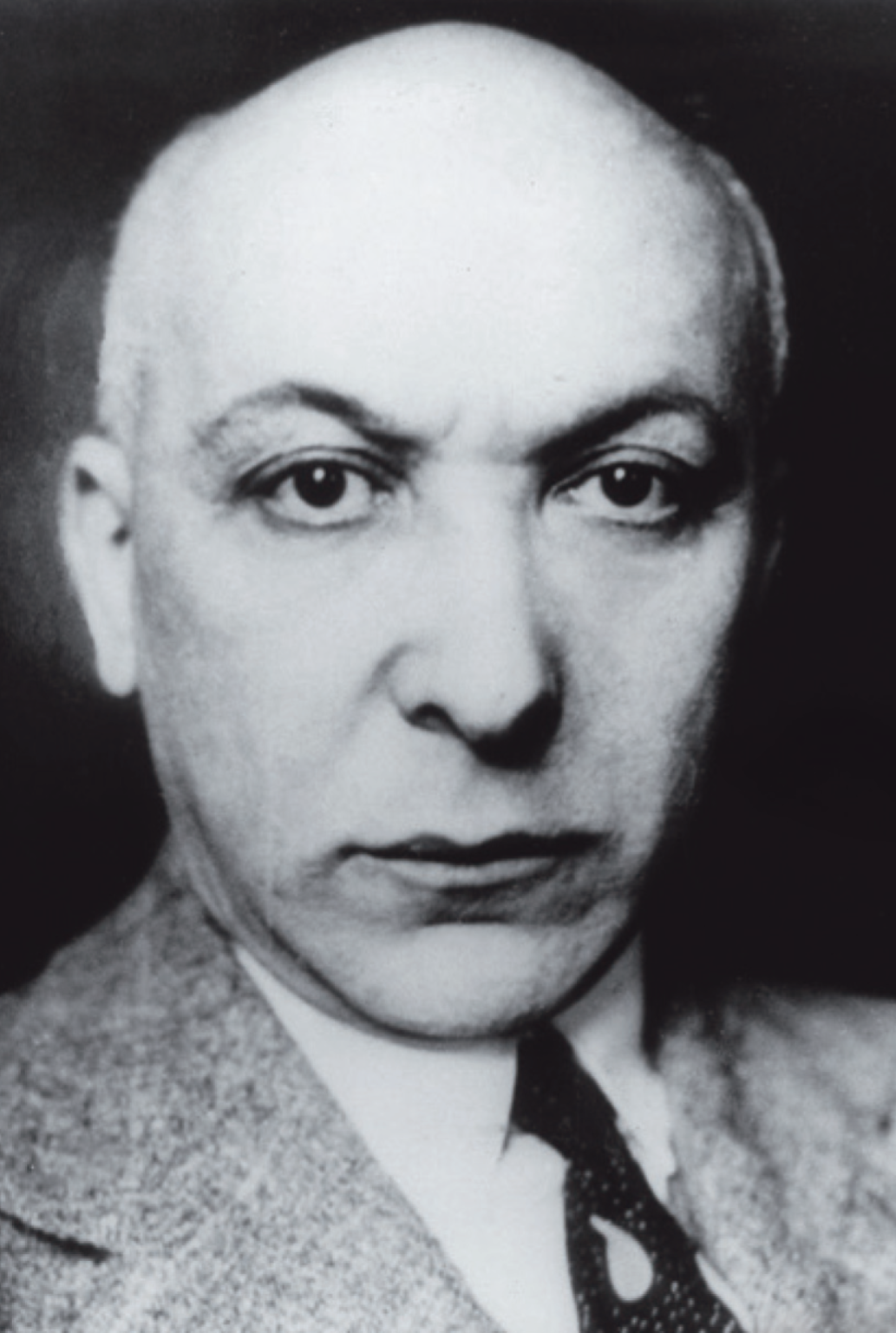

& Franz Hessel (1880-1941)

A Francophile, this Jewish novelist and translator was banned from publishing in Germany when the Nazis came to power, and only left Berlin in 1938 to go into exile in Paris. As the Wehrmacht approached, he moved to Sanary with his wife Hélène, a German painter and journalist, and his son Ulrich. Weakened by two periods of internment, the last in 1940 at the Milles camp, he died on 6 January 1941 in Sanary. ‘He was a brave man’, it was said at his funeral in the town’s old cemetery. His ‘ménage à trois’ was immortalised in the almost autobiographical Jules et Jim by his friend Henri-Pierre Roché and in the film adaptation of the novel by François Truffaut.

Arriving in Sanary in the spring of 1940 with his wife Helen and eldest son Ulrich, Franz Hessel was one of the last exiles to come to the village.

This novelist and literary director of the major German publishing house Rowohlt had lived between Berlin and Paris since 1906. It was in Montparnasse at the Café du Dôme that Franz met Helen Grund in 1912, the youngest of five children from a wealthy Berlin family. They married in 1913 and their future looked promising: Franz had inherited a small fortune that would allow them to live comfortably while pursuing their artistic ambitions. But the First World War broke out and the Hessels, although Francophiles, became undesirable foreigners in Paris. They returned to Berlin, where they moved into a large, beautiful flat and also owned a country house south of Munich. But Franz was sent to the front as an ordinary soldier, and returned at the end of the war scarred for life by his experiences.

The couple now have two sons, Ulrich and Stéphane. They live in their country house, and to entertain Helen, Franz invites his old Parisian friend Henri-Pierre Roché to join them. However, he had no idea of the passionate affair that was to last for some fifteen years between his wife and his best friend. Pierre Roché would later immortalise their ‘ménage à trois’ in his novel Jules et Jim, which inspired François Truffaut to make the iconic french film of the same name.

In 1925 Helen, divorced from Franz in 1921 but immediately remarried to him, moved with her sons to Paris where she worked as a fashion journalist for the Frankurter Zeitung. But she came under pressure in her profession because of her Jewish husband. She divorced again in 1936, to ensure the family’s income. In 1938, however, she was still dismissed. Since the Nuremberg Laws were passed in 1935, Franz had been unable to work in Germany and insisted on staying. He was finally persuaded to join Helen and Ulrich in their small flat in Paris. For the first time, they had no servants and no money. As soon as war was declared, Franz and Ulrich, considered undesirable German nationals, were interned in the temporary camp at the Colombes stadium. While the father was quickly released because of his age, the son remained locked up for another three weeks.

In the spring of 1940, they went down to Sanary where Helen had spent the summer of 1933 and had met Aldous Huxley. Thanks to this contact, they were able to settle first in the Huxleys’ villa in the United States, then they found refuge in the Villa impasse Lou Cimaï, where Franz created his own world in a small square tower to work in. It would be his last place of work and his last home. In May 1940, Franz and Ulrich were sent to the Milles camp. They were released in July, no doubt thanks to Helen’s perseverance. She was convinced that their son Stéphane’s prestigious studies at the École Normale Supérieure gave her family a special status and she demanded their freedom. Franz Hessel came out of his internment very weak and never recovered. He died on 6 January 1941 in Sanary-sur-Mer.

TO FIND OUT MORE

The Jacques Duhamel multimedia library in Sanary-sur-Mer has a collection of books on the theme of the memory of exile in Sanary.